In chapter 14 of How To Pray from HarperOne, C. S. Lewis raises the issue of the benefit of a sacramental understanding of the Creation in which we dwell and worship. The summary question, provided by the chapter heading, is “How Can We Be Like David and Pray with Delight?” The obvious answer is to pray like David prayed. But what did that look like? How might it have differed from the way we pray, as modern westerners? The answer is found in David’s unconscious assumption about God’s presence with us, vis a vis, Creation.

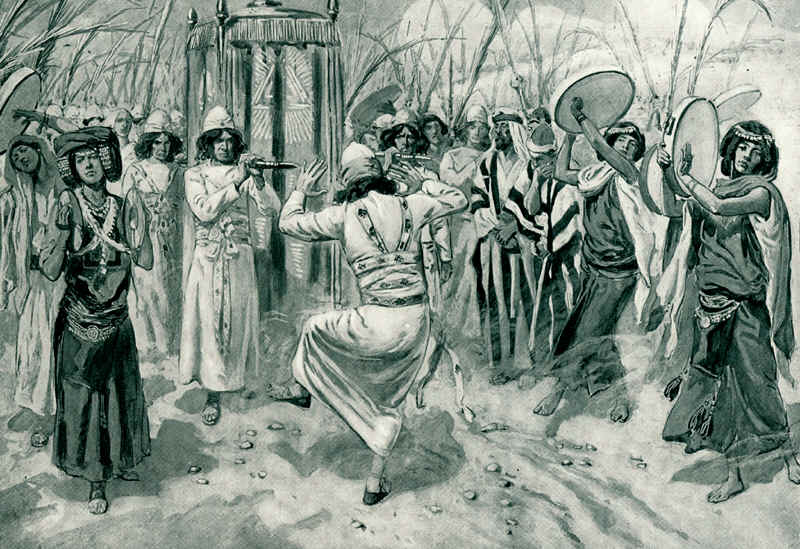

Lewis says he benefits from the Psalms because they illustrate for him a kind of “appetite for God” (p. 120) that he himself desires. Lewis wants to personally and experientially know God, in all his fullness. It seems to him that the ancient Jews had an experience that was richer than what we moderns tend to experience. They had this experience because they were not conscious of some divide between the literal and the abstract. If the ark of the covenant was in your house, God was in your house. The admittedly still spiritual presence of God was not distinguished from some object which in some way was associated with his presence, for whatever reason. The result is that the more sensual part of our being, as humans, is included in our experience of God, not excluded for some philosophical reason.

This interconnectedness of the material and spiritual is something of what is meant when we talk about a sacramental view of the world. The result can be more joy, more delight in our spiritual experience. We can enter more fully into the worship experience which we see in the Psalms – we add rituals, feasting, singing, and dancing to Bible study and prayer.

By the way, we don’t want anyone making the mistake that this kind of thinking excludes the grace of faith. It does not. It is simply a consideration of how faith can engage the promises and presence of God in various ways. Our hearts can take hold of the promises of God and the Gospel story in other ways than merely banking on a chapter and verse of the Bible – though by “merely” I do not mean to lessen the Bible’s proper place of importance. Yet, the Patriarchs walked with God by faith without a Bible at all.

The modern Christian can think this is too “carnal.” He or she can also be concerned about the more tragic element of our adoration of the LORD, living as we do after the life of Jesus. Lewis understands this and admits that, “Our joy has to be the sort of joy which can coexist with that; there is for us a spiritual counterpoint where they had simple melody” (p. 121). But, as he goes on to say, his concern in this essay is to help us to understand what he means by “coexist” with the older view. We need to be aware of the older view and seek to somehow get more experientially inside it, so we can share in that kind of joy of the presence of God.

Lewis doesn’t mention this, but we have to be on guard against a certain kind of hermeneutic – for centuries called Marcianism – which divides the religious belief and experience of the Old Testament saints from the new. We have to remind ourselves that their God is our God. And their experience of him was just as real as ours can be today. “Abraham rejoiced to see my day,” Jesus said. That being the case, our New Testament worship can potentially profit from more of a taste of their kind of worship. Indeed – for those of us concerned about being apostolic – would this not be closer to the worship of the early church? Though western thought was already creeping into their lives, they were still very much children of the Old Testament spirituality – they did keep worshipping in the Temple (Acts 2).

Many western churches, because of their fear of empty or even superstitious rituals, have no rituals at all. A worship service is really just a glorified Sunday School class. The apparent reason for meeting is to learn more about the Bible and have good Christian fellowship. There is no structure or decor about the service that would lead people before the throne of God to worship their King. Would David have recognized that as the worship of God’s people? Maybe, but what would he think was missing?

Does stripping away the historic, centuries-old worship of the Church lead us into a biblical spirit of worship which satisfies more than just our minds or our bare “spirit?” I am not saying you cannot experience God in a service of 3 hymns – don’t forget the announcements! – and a sermon. But what potential is lost if we depart from the traditional liturgy? How does that help us pray as David prayed?

Lewis points us to the Psalms and answers that, if we would pray as David prayed, we will want to increase our awareness of the “sacramentality” of Creation and to taste the presence of God through it, in those places where he has promised to “show up.” We want the distinction between the physical rites and actions and the presence of God to blend, to fade, to be one experience. We want more than to satisfy a curiosity about God. We want to have a hunger for God and to “taste” Him, who is both the Creator and the Redeemer of All.

Reference: C. S. Lewis, How To Pray: Reflections and Essays, (New York, HarperOne, 2018), ISBN-13: 978-0062847133.

————————–

Please note that the content and viewpoints of Rev. Beckmann are his own and are not necessarily those of the C.S. Lewis Foundation. We have not edited his writing in any substantial way and have permission from him to post his content.

————————–

The Rev. David Beckmann has for many years been involved in both the Church and education. He helped to start a Christian school in South Carolina, tutored homeschoolers, and has been adjunct faculty for both Covenant College and the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga. He founded the C.S. Lewis Society of Chattanooga in 2005. He has spoken extensively on C.S Lewis, and was the Director of the C.S Lewis Study Centre at The Kilns from 2014-2015. He is currently a Regional Representative for the C.S. Lewis Foundation in Chattanooga.

The Rev. David Beckmann has for many years been involved in both the Church and education. He helped to start a Christian school in South Carolina, tutored homeschoolers, and has been adjunct faculty for both Covenant College and the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga. He founded the C.S. Lewis Society of Chattanooga in 2005. He has spoken extensively on C.S Lewis, and was the Director of the C.S Lewis Study Centre at The Kilns from 2014-2015. He is currently a Regional Representative for the C.S. Lewis Foundation in Chattanooga.